- Liver Structure and Function

- Evaluation of the Patient With a Liver Disorder

- The Asymptomatic Patient With Abnormal Liver Test Results

- Acute Liver Failure

- Ascites

- Inborn Metabolic Disorders Causing Hyperbilirubinemia

- Jaundice

- Metabolic Dysfunction–Associated Liver Disease (MASLD)

- Portal Hypertension

- Portosystemic Encephalopathy

- Postoperative Liver Dysfunction

- Spontaneous Bacterial Peritonitis (SBP)

- Systemic Abnormalities in Liver Disease

Topic Resources

The liver is a metabolically complex organ. Hepatocytes (liver parenchymal cells) perform the liver’s metabolic functions:

Formation and excretion of bile as a component of bilirubin metabolism (see Overview of bilirubin metabolism)

Control of cholesterol metabolism

Formation of urea, serum albumin, clotting factors, enzymes, and numerous other proteins

Metabolism or detoxification of drugs and other foreign substances

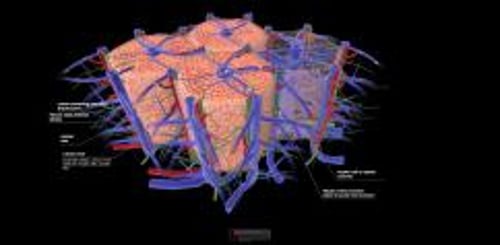

Overview of liver structure

At the cellular level, portal triads consist of adjacent and parallel terminal branches of bile ducts, portal veins, and hepatic arteries that border the hepatocytes. Terminal branches of the hepatic veins are in the center of hepatic lobules. Blood flows from the portal triads past the hepatocytes and drains via vein branches in the center of the lobule, rendering the center of the lobule the area most susceptible to ischemia.

Copyright © 2023 Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA and its affiliates. All rights reserved.

Overview of bilirubin metabolism

The breakdown of hemoglobin produces bilirubin (an insoluble waste product) and other bile pigments. Bilirubin must be made water soluble to be excreted. This transformation occurs in 5 steps: formation, plasma transport, liver uptake, conjugation, and biliary excretion.

Formation: About 250 to 350 mg of unconjugated bilirubin forms daily; 70 to 80% derives from the breakdown of degenerating red blood cells, and 20 to 30% (early-labeled bilirubin) derives primarily from other heme proteins in the bone marrow and liver. Hemoglobin is degraded to iron and biliverdin, which is converted to bilirubin.

Plasma transport: Unconjugated (indirect-reacting) bilirubin is not water soluble and so is transported in the plasma bound to albumin. It cannot pass through the glomerular membrane into the urine. Albumin binding weakens under certain conditions (eg, acidosis), and some substances (eg, salicylates, certain antibiotics) compete for the binding sites.

Liver uptake: The liver takes up bilirubin rapidly but does not take up the attached serum albumin.

Conjugation: Unconjugated bilirubin in the liver is conjugated to form mainly bilirubin diglucuronide (conjugated [direct-reacting] bilirubin). This reaction, catalyzed by the microsomal enzyme glucuronyl transferase, renders the bilirubin water soluble.

Biliary excretion: Tiny canaliculi formed by adjacent hepatocytes progressively coalesce into ductules, interlobular bile ducts, and larger hepatic ducts. Outside the porta hepatis, the main hepatic duct joins the cystic duct from the gallbladder to form the common bile duct, which drains into the duodenum at the ampulla of Vater.

Conjugated bilirubin is secreted into the bile canaliculus with other bile constituents. In the intestine, bacteria metabolize bilirubin to form urobilinogen, much of which is further metabolized to stercobilins, which render the stool brown. In complete biliary obstruction, stools lose their normal color and become light gray (clay-colored stool). Some urobilinogen is reabsorbed, extracted by hepatocytes, and re-excreted in bile (enterohepatic circulation). A small amount is excreted in urine.

Because conjugated bilirubin is excreted in urine and unconjugated bilirubin is not, only conjugated hyperbilirubinemia (eg, due to hepatocellular or cholestatic jaundice) causes bilirubinuria.

Pathophysiology of Liver Disorders

Liver disorders can result from a wide variety of insults, including infections, drugs, toxins, ischemia, and autoimmune disorders. Occasionally, liver disorders occur postoperatively. Most liver disorders cause some degree of hepatocellular injury and necrosis, resulting in various abnormal laboratory test results and, sometimes, symptoms. Symptoms may be due to liver disease itself (eg, jaundice due to acute hepatitis) or to complications of liver disease (eg, acute gastrointestinal bleeding due to cirrhosis and portal hypertension).

Despite necrosis, the liver can regenerate itself. Even extensive necrosis can resolve completely (eg, in acute viral hepatitis). Incomplete regeneration and fibrosis, however, may result from injury that bridges entire lobules or from less pronounced but ongoing damage.

Specific diseases preferentially affect certain hepatobiliary structures or functions (eg, acute viral hepatitis is primarily manifested by damage to hepatocytes or hepatocellular injury; primary biliary cholangitis, by impairment of biliary secretion; and cirrhosis, by liver fibrosis and resultant portal venous hypertension). The part of the hepatobiliary system affected determines the symptoms, signs, and laboratory abnormalities (see testing for hepatic and biliary disorders). Some disorders (eg, severe alcohol-related liver disease) affect multiple liver structures, resulting in a combination of patterns of symptoms, signs, and laboratory abnormalities.

The prognosis of serious complications is worse in older adults, who are less able to recover from severe physiologic stresses and to tolerate toxic accumulations.